Cheesemonger's Corner

Welcome!

Cheesemonger - (noun) /Cheese-mon-ger/ (add pronounciation accents- MS)

- An expert in the smells, tastes, textures, and other intriacies of fine cheese. Trained in the best way to cut, serve, prepare and store cheeses, and the best pairings and flavor combinations.

With our highly trained staff of Cheesemongers, you can rest assured the utmost care is taken to source the finest and freshest (or funkiest!) cheeses to bring to you. We hand-cut and hand-wrap a large percentage of our specialty cheeses the day that your order ships to ensure you get the absolute freshest product possible.

Cheesemonger - (noun) /chēz-mon-ger/

- An expert in the smells, tastes, textures, and other intriacies of fine cheese. Trained in the best way to cut, serve, prepare and store cheeses, and the best pairings and flavor combinations.

With our highly trained staff of Cheesemongers, you can rest assured the utmost care is taken to source the finest and freshest (or funkiest!) cheeses to bring to you. We hand-cut and hand-wrap a large percentage of our specialty cheeses the day that your order ships to ensure you get the absolute freshest product possible.

Meet Your Cheesemongers

Christy Caye, ACS CCP, CCSE

Christy grew up in Northern California, unaware that all along she had been in one of America’s hotspots of cheese production. At 16 she became suddenly and inexplicably fascinated with cheese and started visiting the cheesemakers and cheese shops in that region, vowing to become a cheese connoisseur. Since then she’s worked at cheese counters in the U.S. and abroad, made cheese on a tiny island off the coast of Ireland, carried wheels of cheese through French Quarter alleys to reach New Orleans chefs, competed in the Cheesemonger Invitational, and became one of only 47 people to hold the American Cheese Society’s most advanced cheese certification. These days she enjoys making sure that every piece of cheese going into a Gourmet Dash box is simply perfect.

Robin Williams

Robin began his cheese career at the famed Inn at Little Washington in Virginia. Realizing he could differentiate himself by learning to work the cheese cart at the restaurant, he unsuspectingly turned himself into a passionate cheese professional. After managing various cheese counters across the Eastern seaboard, he ended up in Atlanta where he helped run the city’s best cheese counter at Alon’s Bakery, sharing his infectious smile and cheese knowledge with anyone at the counter. These days he loves doing complicated math equations to extract perfect cuts from a wheel of cheese and occasionally showing off his “perfect cut dance.”

The Four Ingredients of Cheese 101:

Possibly the most interesting thing about cheese is how much variation can be created from the same four ingredients. Cheese, unless added with additional flavoring (fruit, herbs, etc), is made of only 4 ingredients. These 4 ingredients can be coaxed into thousands of types of cheese that are wildly different in flavor and appearance. Here’s a quick rundown of the big four, and the role each plays:

Milk: Cheese is basically just milk without water. The purpose of cheesemaking, a.k.a. removing water from milk, is to delay spoilage and preserve the nutrients in milk for future consumption. Milk is mostly made of water, protein, fat, and sugar. Cheesemaking creates conditions where the protein and fat solids in milk can separate from the water, so the fat and protein can become cheese. After this process, a cheesemaker is left with curds, made of mostly fat and protein, and whey, made of mostly water and sugar.

Rennet: Rennet is the tool cheesemakers use to separate water from milk. Renet is an enzyme that changes the chemical bonds in milk so that the protein and fat can separate from the water and sugar. Rennet can come from a variety of sources. It’s usually taken from the stomach lining of a young ruminant animal, like a cow or goat. It can also be found in some plants like thistles, which can be used to coagulate milk. There’s also microbial rennet, which is developed from types of fungi. Rennet derived from plants or fungi is considered the vegetarian alternative to traditional rennet.

Culture: In the cheese world, “culture” refers to different blends of bacteria that cheesemakers add to create a desired type of cheese. Cultures not only help cultivate certain flavors and texture, but they also help outnumber other undesirable bacteria, which helps preserve the cheese. Different culture blends are added to the cheesemaking process depending on the type of cheese being made.

Salt: Makes cheese tasty, yes, but also very important for food preservation. Salt also affects the pH balance of a cheese, which plays a big part in its evolution into different styles.

By Christy Caye

How Does A Cheese Get Its Name?

It’s all about location!

Historically, cheeses were named after the village where they were made. Cheese made in the town of Stilton, for example, was considered simply the cheese from Stilton, or “stilton cheese.”

Common styles of cheese made beyond just one village were often named according to the region where they were produced. Such as, Pecorino Romano, which means "the pecorino of Rome." Or Tomme de Savoie: "the tomme style of cheese from Savoie, France. Cheeses like Gruyere, Roquefort, and Emmentaler are all named after their place of origin.

Cheesemakers are more creative nowadays – especially since some towns have multiple creameries that make different kinds of cheese. They can’t all have the same name, of course! Even so, American cheesemakers still find inspiration in their surroundings, using names like “Humboldt Fog” or “Appalachian” that keep the old tradition. Others like “Fat Bottom Girl” or “Intergalactic” prove that modern cheesemakers aren’t afraid to have more fun with their names.

By Christy Caye

The Cheesemaking Origin Story: Probably A Myth

Many cheese writings tell a familiar story of how cheese was probably discovered. To understand this story you have to know that cheese is made of milk, and chemically transformed into cheese using an enzyme from a young ruminant animal’s stomach, which transforms milk into curds and whey.

The story goes like this: An ancient traveler put milk into a commonly used type of carrying bag: one made of an animal’s stomach. While he traveled across the desert (warm temperature is important here), the milk sat in the stomach-bag and jostled around. At his destination, he opened the bag to discover that instead of fluid milk, he had curds and whey. Though he didn't know it, the heat and enzyme in the animals' stomach (rennet) transformed his milk into cheese. Such is the accidental birth of cheesemaking.

According to Paul Kindstedt in his book Cheese and Culture, around the time cheesemaking was developed, most adults were actually lactose intolerant. Which means they were probably keeping goats and sheep around for their meat and wool only. Adults trying to drink the milk would have gotten very sick. That’s why it’s very unlikely a traveler would have packed milk as a long-journey food provision.

The more likely story is that people probably started feeding animal milk to children, who could still digest lactose. When left sitting, milk does curdle on its own without the help of the enzyme rennet. It’s more likely that adults eventually tasted some old curdled milk and discovered the curds didn’t make them quite as sick, allowing them to ingest a dairy product comfortably. This is because curds, and therefore cheese, have less lactose than fresh milk does. Cheesemaking probably advanced from that point on, along with the evolution of more prominent lactose tolerance in adults.

By Christy Caye

How do I know when to eat the rind?

Though the world of cheese rinds is complicated, there is one foolproof reference for knowing how and when to eat a cheese rind: ask yourself. Sure, some people may say “you’ve gotta eat that rind, it’s the best part!” Others may say “That rind looks too scary to eat”. Surprisingly, there are no official rules about which cheese rinds should or should not be eaten.

Sure, there are rinds more commonly eaten because it makes practical sense. For example, a mini wheel of brie has a large percentage of rind. Remove it and you won’t be left with much at all.

There are other rinds that aren’t really meant to be eaten, but these are fairly intuitive. Think wax, wood, straw - these are things that probably wouldn’t hurt you, but the cheesemaker didn’t intend for you to eat them. On the other hand, some cheeses have leaves on the outside. Since the leaves are thin, tender, and possibly soaked in some kind of booze, these are easy to eat, though might exist in the gray area of “should I?”.

Bottom line: Look at the rind. Smell the rind. Does it look appealing? Taste it. If you like the flavor, proceed. If you don’t, dont. There are no shoulds and shouldn’ts, just your own personal cheese eating journey. Your cheese, your choice!

By Christy Caye

Cow, Goat, Sheep? Don't Forget About Breed

Many seasoned cheese eaters are familiar with the differences between cow, goat, and sheep's milk cheeses. (There are other cheesemaking animals too - we can’t forget the humble water buffalo, or the occasional donkey.)

But did you know that animal breed is a significant factor in the history of great cheese and the practice of modern day cheesemaking? Believe it or not, there is major variation in the flavor and composition of milk between breeds. Yes! The flavor of a Saanen goat's milk is different than that of a Nigerian Dwarf goat.

Some cheeses are even required to be made with milk from one specific breed of animal only. Take Manchego - this is a Spanish sheep's milk cheese from the La Mancha region of Spain. By Spanish and E.U. law, Manchego must be made with the milk from the Manchega breed of sheep. Since this cheese is traditionally from this region, and the region had mostly Manchega sheep going back hundreds of years, it is believed that a version made from a different type of sheep milk wouldn’t be an authentic Manchego.

Even the cheesemakers in the U.S., with a shorter cheesemaking history than other places, select different breeds depending on the need. Holstein cows - the white ones with big black spots - produce a lot of milk. Their volume is much higher than other breeds. Cheesemakers looking for lots of milk will choose Holsteins for cheesemaking.

On the other hand, some cheesmakers will choose a Jersey cow, a breed with a sweet face and a light brown coat. Jerseys produce less milk by volume, but the milk is richer, which some artisanal cheesemakers prefer.

Next time you hear breed mentioned, don’t be surprised. If you ever visit a cheese farm, ask about what breeds are on the farm - you tour guide will probably be delighted to discuss this fun topic.

By Christy Caye

How Much Cheese Should I Buy and Serve for a Gathering?

The general rule of thumb is 1-4 ounces, per person, per cheese. This is a good starting point, but still a pretty wide range! Let’s look at how different scenarios can let you know whether to go with the lower or higher end of that range.

When you’re thinking about the gathering, ask these questions:

- How many types of cheese will be served? If it’s a cheese board of 3 types, people will eat more of each kind. If you’re offering many varietes, say 5-10 types, your guests will taste more varieties, and will probably eat less of each.

- Answer: When there’s more variety, budget less of each type per person.

- What part of the day or event is this being served? Is this an after-dinner cheese course? People will eat less cheese after dinner when they’re full than if they are served cheese before a meal.

- Answer: After or during a meal: stick to the lower end of the range. Before a meal: lean towards the higher end of the range.

- How much other food will be there? Is this a wedding reception with a dinner buffet near the cheese? Or the cocktail hour with only drinks and cheese? What about the accompaniments? Will there be a huge spread of bread, crackers, charcuterie and more? Or just a few cheeses and some crackers?

- Answer: When there’s less other food at the event, budget more cheese per person.

By Christy Caye

Let Cheese Guide your Next Vacation

Following the cheese always leads to incredible experiences. Here are some cheesy places and events that are well worth a detour:

- Slow Food Italy’s “Cheese” Festival: Held every other year in the town of Bra in northern Italy, this event draws cheese professionals and cheese lovers from all over the world. Visitors to this quaint Baroque-style town can wander the narrow streets and immerse themselves in all kinds of cheese festivities. (Every other September, Bra, Italy).

- The Caves of Roquefort: Head to this rural corner of Southern France to a town called Roquefort-sur-Soulzon, where blue cheese was practically invented. The mold in most of the world’s blues, Penicillium roqueforti, is named after this village. This is also the place where the ancient blue Roquefort is still made and aged in caves – which you can visit! Check out a cave tour here and you’ll never think of blue cheese the same way again. (Year-round).

- The Autumn Cow Parade in the Alps: Cows bedecked with flower crowns and ornate bells descend from mountain pastures back into their village where they’ll spend the winter. This occasion is marked with a festival of food and celebration to observe the moment when all the cows come home. (Between late August and October in Switzerland, Austria, and parts of France).

- Cooper’s Hill Cheese Rolling: A world-famous yearly event in Gloucester, England, where a wheel of Double Gloucester cheese is rolled down a very steep and uneven hill and then frantically chased by participants. (Every Spring, Cooper’s Hill England).

- Cheese Shops of Paris: The French are arguably the best at making cheese. If that’s true then many of the world’s best cheeses are all brought together in the hub of French society: the 40 square miles of Paris. A day visiting cheese shops around Paris is a sure way to try some of cheese’s most incredible examples and enjoy a life-changing experience. (Year-round, Paris, France).

- Alkmaar Cheese Market: For a true spectacle of cheese, visit the Netherlands to see a cheese trading market in operation since 1365. Here you can see cheese “tossers”, “porters”, and “weighers” dressed in traditional clothes who move around thousands of wheels of gouda in the tradition of weighing and trading wheels. (April to September, Alkmaar, Netherlands).

By Christy Caye

Why is this cow wearing a flower crown?

Imagine a place where flat land is scarce. Rugged terrain and long snowy winters make growing crops difficult.

Then you hear a friendly, “Moooooo.”

Here, in the European Alps, cows have managed to carve out excellent pasture in otherwise arid terrain. Their milk contains precious nutrients, especially when transformed into cheese that can feed an entire village throughout the rugged winter.

This resiliency in cows has created a reliable food source for centuries – and birthed an adorable tradition.

Each spring, when the snows melt, alpine villagers send their cows high up into the mountains, where they stay all summer with a person or two who will care for them and make cheese from their milk. In autumn, the whole herd slowly walks down the mountain in a festive parade back to town that’s meant to celebrate the cows and the fruits of their labor: delicious cheese.

On this special occasion, the cows are adorned with flower crowns and big bells that create a joyous – and meaningful – display. The lead cow is called the “Kranzrind, or “crown cow.” She wears the biggest crown and bell of all.

The “Alpine” cheeses are types that were born of this tradition. Today similar cheeses are made outside the Alps, but still considered Alpine in style.

It’s the dream of many a cheese professional to witness this spectacle first-hand during their lifetime. Talk about cheese tourism!

By Christy Caye

10 Important Things to Know About Cheese

- Cheese is basically milk without water. Cheesemaking is a process that removes water from milk, leaving behind the solids like protein and fat, allowing those nutrients to be preserved much longer and delay spoilage.

- In order to make great cheese, a cheesemaker must start with great milk. This is why any conversation about cheese includes discussion of the farm and animals where it all begins.

- So many factors affect the way a cheese tastes, starting with atmosphere and soil on a farm, species and breed of animal, milking process, cheesemaking, aging, how the cheese is packaged and served, and every little thing in between.

- Historically cheeses were named after the place they were produced. The Swiss town of Gruyere, or the English town of Stilton, for example. These days some cheesemakers stick to that tradition, but many pick fun names for their cheese, like “Death and Taxes” or “Ewe Calf to be Kidding” for example.

- Pasteurization wasn’t developed until the late 1800s. All milk and cheese consumed for thousands of years before then were raw.

- In the U.S. raw milk cheese cannot be sold under 60 days old.

- A “farmstead” cheese is one made on the same property where the animals are milked, and the company or family in charge of the milking is also in charge of the cheese production. The comparable term in wine is “estate bottled.”

- Natural cheese colors include white, light yellow, and golden hues. Any other color is added to the cheese. A common coloring agent called annatto is responsible for orange cheese.

- Cheddar is both a noun and a verb. Cheddar is cheddar because it has been cheddared.

- There are thousands of different types of cheese made from only four ingredients: milk, rennet, culture, and salt.

By Christy Caye

What is a “Clothbound” Cheddar?

Walk in any fine cheese shop and you’re likely to find a clothbound cheddar for sale. This is simply a cheddar which has been aged in cloth, a seemingly minor factor that has significant impact on the final flavor of the cheese.

Since cloth is not airtight, the cheese aged this way will lose some of its moisture to evaporation. Less water means the cheese will be firmer, drier, and more crumbly. More importantly, the less water that’s present, the more concentrated the subtle flavors will be, showcasing more of the cheese’s complexity and depth. This process can’t happen when cheese is aged in vacuum-sealed plastic.

During aging a cloth-wrapped cheese is sort of “breathing” with its environment. It’s constantly absorbing flavors of its surroundings. Historically these cheddars were aged in cellars, stone basements, or caves, giving them earthy, wet stone aromas and flavors. Cheddars aged this way today taste most closely to how the original cheddars tasted in England hundreds of years ago. For those into history and culture, a bite of clothbound cheddar is kind of like a time machine!

or a fun experiment, try tasting a regular aged cheddar and a clothbound cheddar side-by-side, and see what differences you notice.

By Christy Caye

An Intro to Raw Milk Cheese

Almost all milk consumed in the United States today is pasteurized. But pasteurization is very recent in the long history of human dairy consumption, only developed in the late 1800s. This is why many cheese lovers consider raw milk cheeses to be more authentic representations of the cheese types originally made before that time.

● Some argue that pasteurization kills not only pathogens (a.k.a. disease-causing bacteria), but most of the place-specific microorganisms that give a cheese its unique flavor.

● Some people also believe that pasteurization offers cheesemakers a false safety net which allows them to handle milk without the careful attention that is required from a cheesemaker handling raw milk.

● The FDA regulates that no cheese made with raw milk can be sold in the U.S. before it’s 60 days old. This is why some young raw milk cheeses made in foreign countries cannot be imported into the U.S. Likewise, if an American cheesemaker makes a cheese from raw milk, they cannot sell it before day 60.

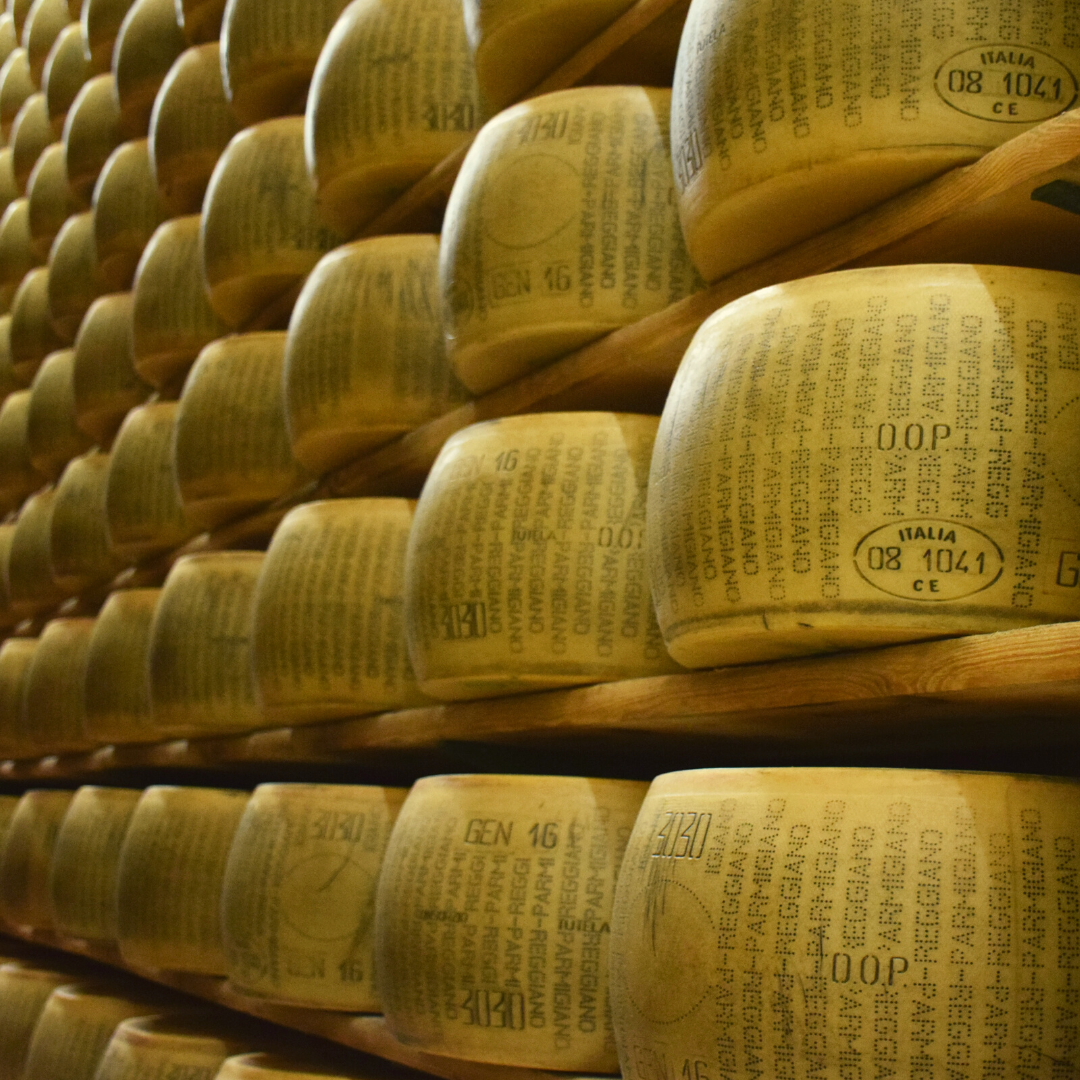

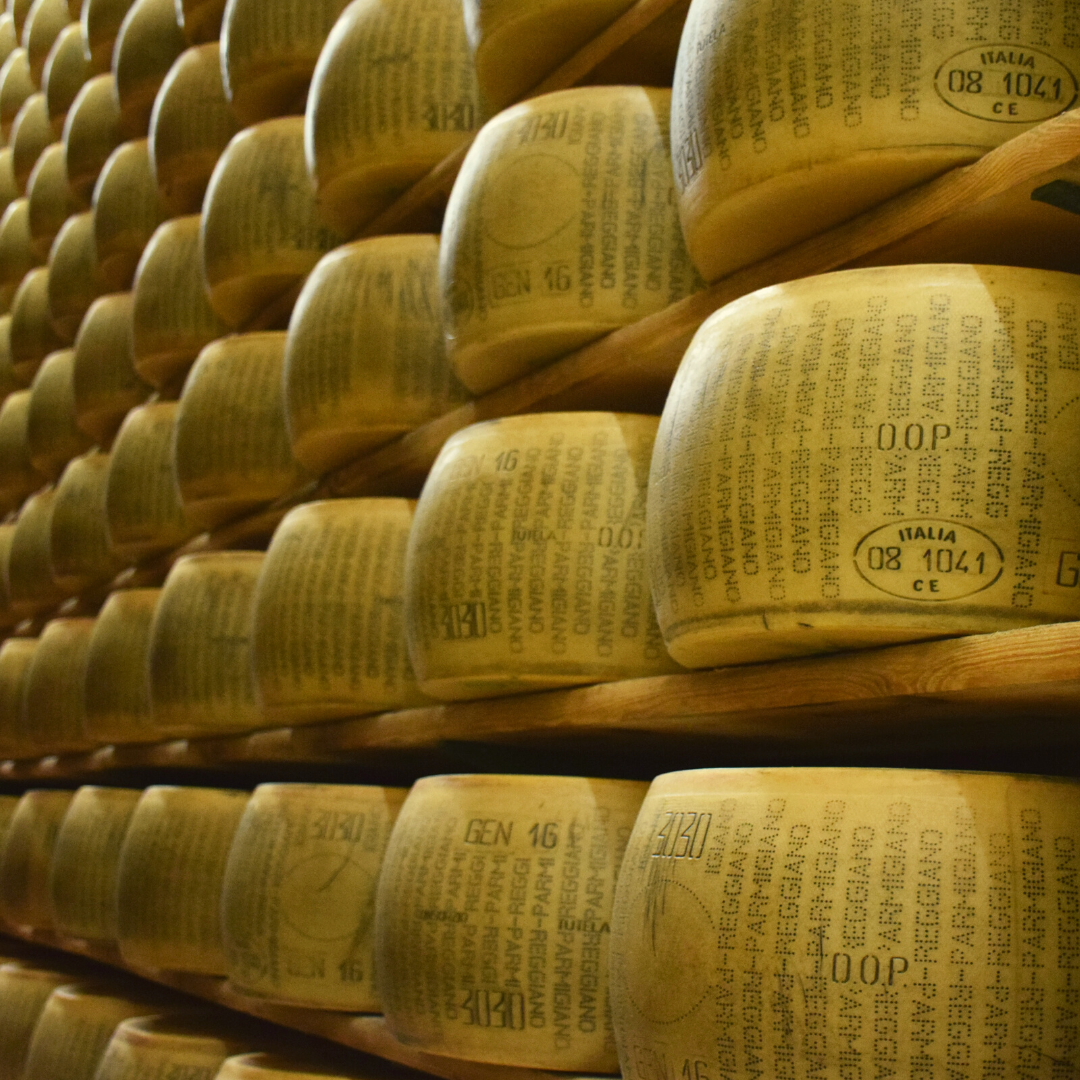

● Most people eat raw milk cheese regularly and don’t think about it. For example, all Parmigiano Reggiano is made with raw milk according to mandatory production standards in Italy.

By Christy Caye

How to Taste Cheese Like a Professional

- Start with your cheese at room temperature.

- Look at your cheese.

- Notice the color

- Notice the texture

- Does it have a rind?

- Smell your cheese:

- Take your bite and break it in half. Take a deep whiff of the fresh edges where it broke. That’s where you’ll get the clearest aroma.

- Smell the rind if there is one. Does the rind smell different than the cheese?

- Taste the cheese without rind: slowly put the cheese in your mouth and let it warm up. Note whatever flavors you taste first.

- As you slowly chew, ask yourself:

- Does it taste different than how it smells?

- What is the texture like?

- Is the flavor changing over time?

- Once you’ve eaten your cheese, don’t rush on. Consider:

- Is there an aftertaste?

- Does the flavor disappear quickly or have a long finish?

- At this point, you can taste a piece with rind if the rind looks appealing to you.

- Draw some conclusions:

- What did you like about it?

- What didn’t you like about it?

- Was it surprising in any way?

Other tips:

- Pairings are fun, but your first taste of any cheese should be on its own.

- If you’re tasting a series of cheeses, start with the mildest one first and leave the strongest for last.

- Between different cheeses, or even bites of the same cheese, you can cleanse your palate with a sip of water and a bite of plain bread or cracker. The bread will help pick up any lingering flavors in your mouth so that you’ll have a clean slate for the next cheese.

- Try tasting two cheeses of the same style together.(Two cheddars, for example.) It’s easier to notice differences with two types side-by-side than if you taste one on its own.

By Christy Caye

PDO, DOP, AOC, OMG - What do acronyms mean after a cheese’s name?

Just like wine, many cheeses have a little acronym on the label that you might not even notice. And just like wine, this denotes that the cheese has come from a specific place and was produced in a particular way that’s mandated by the appellation. A good example is Manchego, which can only be made in the La Mancha region of Spain with the milk of the Manchega breed of sheep.

It’s also important for regulatory reasons. When a cheese’s name becomes protected in production, anyone buying a cheese with that title knows they’re getting an authentic representation of that type.

Check it out on a label next time you buy cheese. Many countries have their own, but here are the most common ones to look for:

P.D.O. - for a cheese recognized by the European Union, meaning “Protected Designation of Origin.”

D.O.P. - for a cheese made in Italy, meaning “Denominazione di Origine Protetta.”

A.O.C. - for a cheese made in France, meaning “Appellation d'Origine Côntrolée.”

On Spark Birds and Spark Cheeses

By Christy Caye

I recently learned about a term the birdwatching community uses: “spark bird.” A spark bird is a person’s first-bird-love, the bird that sparked their passion for birdwatching and changed their perspective on birds forever.

A cheese version of this term makes sense too. Many cheese lovers have a memory of one particular cheese that changed their understanding of cheese. Our cheesemonger Robin remembers his own spark cheese moment, when someone handed him a piece of Pont L’Eveque.

He recounts being flabbergasted: “That was cheese? I had no idea cheese could taste like that.” From then he was on a quest for cheese knowledge which continues to this day.

There’s another type of spark cheese, with a slight variation. This spark cheese is more mysterious and elusive. Cheesemongers often experience a particular customer: one who approaches the cheese counter and describes with eagerness a type of cheese they had in such-and-such place a long time ago. Maybe they had it on a trip to Italy, but don’t remember the name. Or perhaps it was something their mom colloquially called “salad cheese” and served them as a child. But even though the memory is strong, the vague details aren’t enough to find that cheese again, even for an expert.These searchers get that faraway look in their eye, for the spark cheese that they search for, that might never be known again.

That’s the nice thing about cheese, and food in general. It has the ability to create a spark. Those feelings and nostalgia that can last a lifetime - whether it’s for the cheeses we ate as kids, the unusual ones we had in faraway places, or just the ones that make us stop and say, “Hey, cheese is cooler than I thought”.

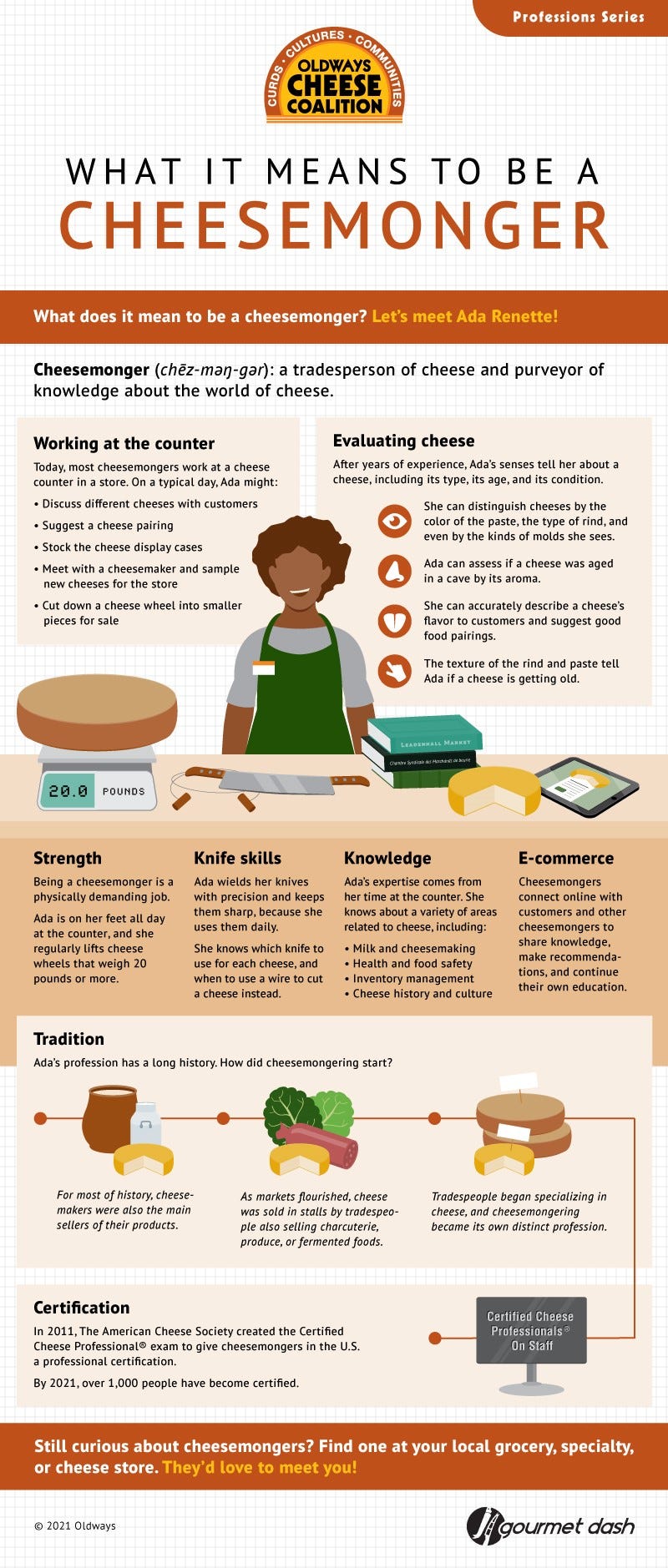

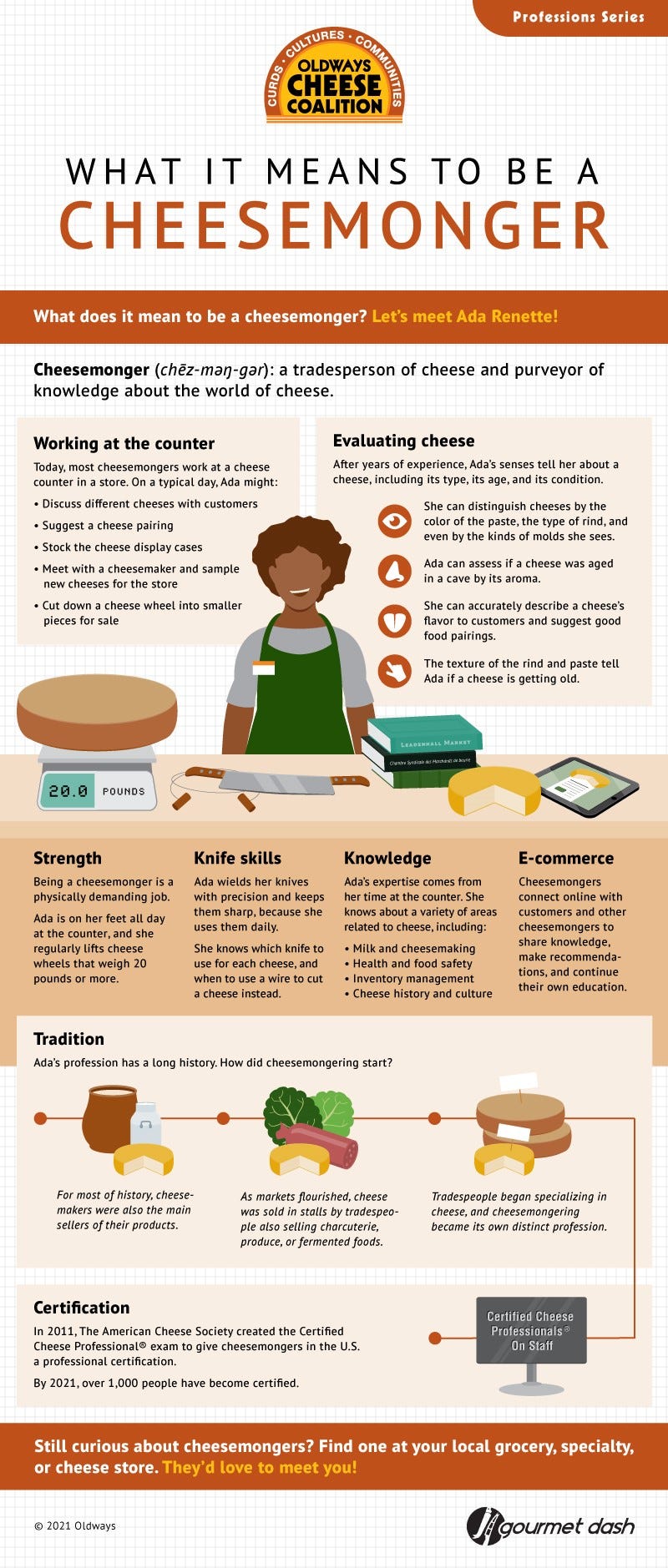

What Is A Cheesemonger?